DAFT*: The opposite of SMART goals for creative work

Goal setting for creative projects is a bit more than being SMART. Here's what else creatives should consider when guiding your process.

Overview

Hello, creatives! My name’s Jamey, and in this article, I’m going to help you grow your knowledge on creative goal setting. More specifically we’ll explore:

- Why goal setting is an important part of the creative process

- The two main flavors of goals — outcome and process goals — and what they help achieve

- Today’s prevailing wisdom on the “right way” to set process goals (hint: it’s SMART)

- How being SMART at the wrong times may actually inhibit creativity

- What DAFT* goals are, and how they help you create things that are unique and novel

- When to use DAFT* goals, and when to use SMART goals

- Where these goals fit in the bigger picture

There’s just enough time to explain! Come on in and let’s get started.

Do any of these sound familiar?

Goal setting isn’t the sexiest part of making things — particularly creative things — but it serves a valuable purpose: Goals help you stay the course when self-doubt tries to push you off the path towards finished creative projects you love.

Without strong goals, it’s far too easy for doubt to creep into your internal dialogue. Do any of these sound familiar?

- “Is what I’m making any good?”

- “I like this but I don’t know where it’s going…”

- “This isn’t as good as that other thing I like.”

- “I feel like what I’m making is just like everyone else’s thing.”

These feelings don’t have to be constant for them to be damaging to your creativity. All it seems to take are a few moments of strong self-doubt and you’ve scrapped the project, called your best friends crying, and gone out for many, many adulterants to take your mind off things… or, so I’m told 😅

If you want to reduce the impact of these moments of self-doubt and strengthen your ability to set goals geared towards creativity (a bit different than the goals we learn to set in school) then read on. Let’s explore this together.

The different flavors of goals

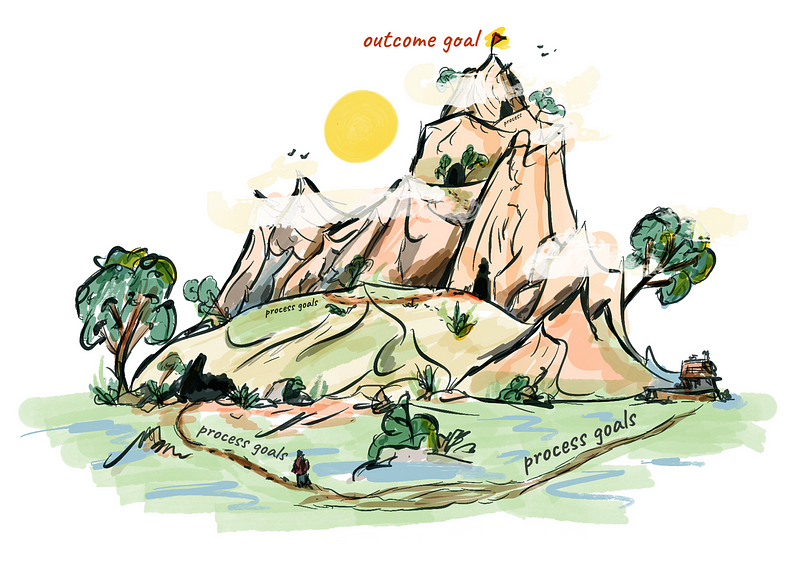

When it comes to the goals we set, there are two main types that nearly all other types stem from — outcome goals and process goals.

Outcome Goals

Outcome goals are the ambitious goals you set in all caps. When you achieve them you get to shout it from the rooftops!

A substantial task — subjected to conditions of time, quantity, and/or quality — that one aims to achieve in the future. Typically requires supporting processes and sustained progress over a period of time [1].

The achievement of outcome goals is usually determined as an accumulation of contributing processes (and/or intentional process goals).

A few examples of outcome goals are:

- Release your debut feature film

- Publish your 3rd book to the marketplace

- Deploy the first version of your app to production

Outcome goals serve the valuable purpose of illuminating our larger ambitions in big neon lights at the finish line. They are the flag at the summit, the treasure in the shipwreck, and the heartwarming resolve set to epic music in the closing scene.

Outcome goals are important because they represent the creative person you’d like to be.

Process Goals

Sitting opposite outcome goals are process goals. These are the lowercase italicized goals that you set day-to-day, week-to-week, and beyond to help you pursue your outcome goals.

An intentional, controllable task subject to conditions of quantity, quality, and/or time that one aims to achieve in the future — often repeatedly — in pursuit of a change or result.

Process goals typically move us closer to a larger ambition or identity, whether intentionally or subconsciously. For this reason, process goals often support outcome goals.

A few examples of process goals are:

- Submit your screenplay to 4 production companies per week

- Write 50 minutes daily towards your next novel

- Fix 2 bugs per commit in your app

More often nowadays you’ll also hear that those process goals should be SMART, which stands for Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant (Reasonable), and Time-bound [2].

These SMART goals often shape the habits and routines you use to move you closer to bigger milestones. Unfortunately, process goals are also often ignored or poorly defined, which can hamstring your motivation and cause even the most well-intentioned goal setter to abandon projects.

It’s worth noting that both outcome goals and process goals are essential if you’re trying to maximize your success in achieving something [3]. But, to make the biggest impact on your creativity, we need to look closer at re-tuning your SMART process goals.

It turns out — at certain points in the creative cycle — SMART process goals might actually be secret saboteurs.

At the start don’t be SMART

SMART process goals often rely on knowing what to do, putting it in your control, and then executing the goal based on the knowledge that it works; it’s the “right way” to do something.

This act of predicting your success in a task with the methods you already know relies heavily on a type of thinking called convergent thinking.

Thinking which aims to arrive at a singular, correct answer to a problem, typically searching for the best solution by using existing knowledge and associations.

Convergent thinking works best when a solution already exists (or can be easily figured) and can be achieved by following set steps/decisions [4].

To some degree, you have to be able to think through a SMART goal to set one. If that weren’t the case, how else will you know if the goal is reasonable? When setting SMART goals, you need some degree of confidence that the process you’re defining will work. And we often look to existing solutions to do this.

Why does this matter? Because novel creativity often requires a different type of thinking.

A large part of the creative process relies on you having new ways of thinking and doing things. Creativity loves a fresh perspective. This fresh perspective gives your creations their novelty; the uniqueness of what you produce.

The type of thinking that often leads us to novel ideas is called divergent thinking, and it’s the polar opposite of convergent thinking.

Divergent thinking is looking beyond what you know to imagine new associations, information, and methods to propose a new answer or solution to a problem.

This thinking is usually non-linear and works best in situations where exploration can lead to unexpected connections and outcomes [5].

Divergent thinking deviates from thinking that there’s a “right” or “best” way to do something, and instead asks exploratory questions like “how does this work” and “why is this the way it is” [6]. This is important when setting goals around creativity because divergent thinking needs some degree of uncertainty — of discovery and adventure — to arrive at novelty.

Well crap. Here we are with two opposing concepts.

Process goals, which work best when they’re SMART, meaning they work best with convergent thinking. And creative novelty, which emerges in places where divergent thinking has room to breathe.

What 👏 should 👏 we 👏 do 👏 ?

There are definitely parts of the creative cycle where SMART process goals help… technical revisions, implementing a marketing plan, registering your works, or planning a release. These are all processes where we’re tooootallly okay with using the common “right way” to do them; novelty be damned, I want my release schedule to look ✨ correct ✨.

Do we throw away SMART process goals?

No! Luckily, we don’t need to trash anything. Remember that — just like outcome goals — SMART process goals are an important piece of the goal-setting puzzle.

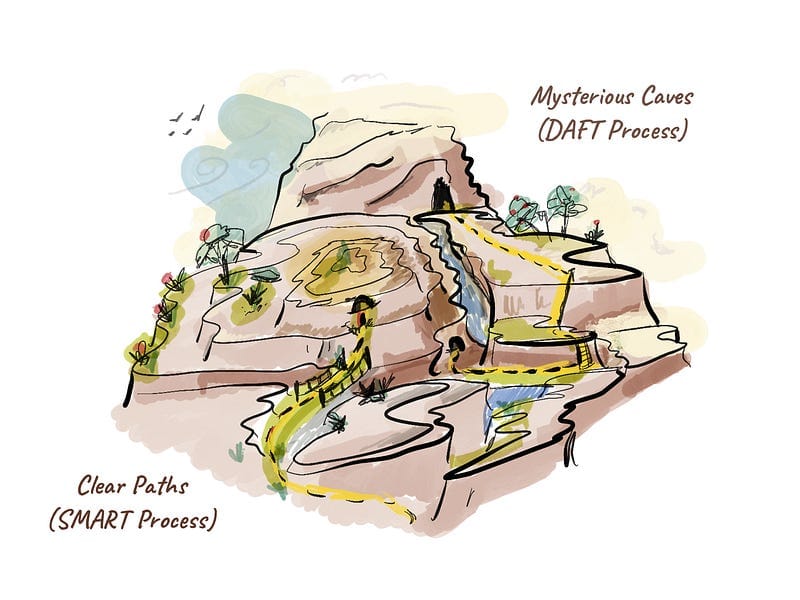

We just need a type of process goal that fosters creativity and gets us to the part of our creative cycle where we’re okay doing things the normal way. We need to be DAFT*.

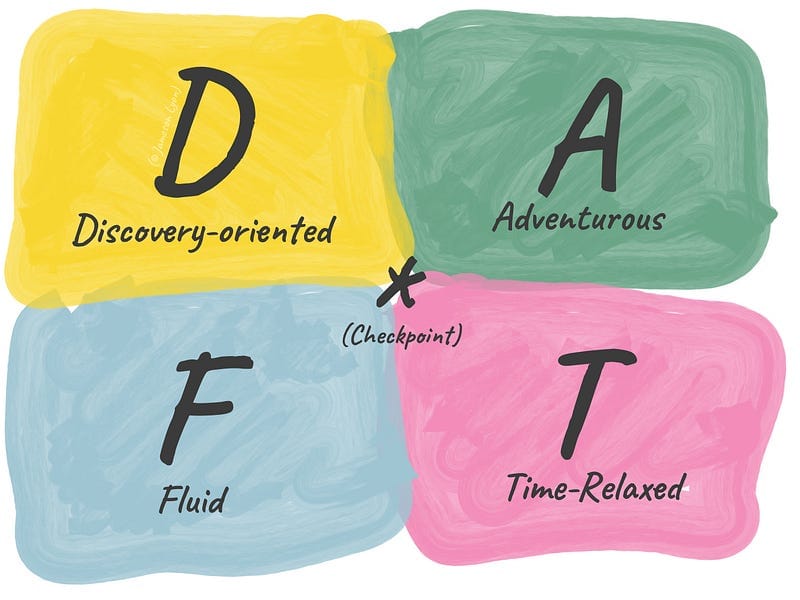

The perks of being DAFT*

Before employing SMART process goals, we need to employ process goals that allow us room to creatively breathe — to step outside the box and look around. Enter DAFT* process goals.

DAFT* is a framework you can use when setting creativity-oriented process goals. It’s my contribution to (what appears to be) an opportunity for clarity between great concepts like learning goals [7, 8] and the types of framing that divergent thinking calls for.

The acronym DAFT* stands for:

- Discovery-oriented

- Adventurous

- Fluid

- Time-relaxed

- * (Checkpoint)

Yes this acronym has an asterisk, it’s an edgy lad 🤓 Let’s look a bit closer at each of these components.

🔭 Discovery-oriented

A process goal that is discovery-oriented acknowledges the unknown nature of what you might stumble upon creatively. Instead of saying “this is what I’m looking for”, a goal that is discovery-oriented says “I wonder what I’ll find.”

When you discover something while following a DAFT* goal, be sure to note it so you can come back to it in the future, like you’re drawing a map.

🚀 Adventurous

Hand-in-hand with discovery-oriented, the adventurous aspect of DAFT* goals asks you to take risks and step out of your normal process.

An adventurous process goal might be to intentionally (and non-destructively) break a “rule” within your craft, just to see what happens. Or pulling on a thread that — while it breaks convention — seems intuitively interesting.

Importantly, adventurous process goals have little expectation of what will happen. Instead, you’re trying to enthusiastically step into the unknown and remain open to what you encounter. Be the curious cat.

🌊 Fluid

If — early in your process — you encounter something which sheds new light on your outcome goal, you’ll want to integrate that perspective and adapt. Fluid process goals do exactly this.

Goals with fluidity remind you that it’s okay to make a lot of adjustments and redefine your goals as you adventure and discover more about your creative undertaking.

Like water that encounters a boulder, fluid process goals move around obstacles as they flow forwards.

🌴 Time-relaxed

Process goals that are time-relaxed have soft deadlines or — taken to a further degree — a deadline that’s yet to be defined.

Procrastination and external time commitments or restraints are perhaps the biggest enemies of time-relaxed process goals. However, we know that putting creativity on a clock can lead to poor performance and outcomes [9].

To counter the risks of procrastination and time pressure, aim to be proactive in the DAFT* part of your creative process. Methods like time blocking may help here by simply putting “discovery” time into your calendar.

Just try to avoid goals like “Have 10 creative insights by Friday” while in the early, creative genesis stages of your projects.

✳️ * (Checkpoint)

Finally, because DAFT* goals are built to be qualitative rather than quantitative, you’ll need something to indicate to you that it’s time to move on to SMART goals. This is the job of the * (checkpoint).

You can think of this as your northern star, or break case (if you love a good while loop) that you’re always checking in on while progressing your DAFT* goals.

A good checkpoint tells you exactly what conditions you have to satisfy in order to safely move on to SMART goals.

Remember, moving on to SMART goals will bias you towards convergent thinking, the opposite of the more creative divergent thinking. So take some time to make sure your checkpoint leaves you with enough creative material to carry the momentum forward.

A sample DAFT* goal

To better illustrate what this looks like, here are some examples of rotating DAFT* process goals that an artist might cycle through while in the early stages of a creative project. I’ve also included the outcome goal for context.

Outcome goal: Release a 5 song EP by the end of the year

DAFT* process goals:

- Explore art styles that match jazz music

Sit down with Alana and jam co-write ideas a few times Alana on tour

☝️ This is what a fluid goal looks like; dropped with a good reason- Stream-of-consciousness write on themes from last year’s vacation, see what comes out

- Jam and noodle on guitar/vocals, drop good ideas into “Punk EP” folder

- Be sure to label key, tempo, and save the project file as the idea name!

- When you have your producing software (DAW) open, break as many rules as you can think of for ≥ 5 minutes

- Research punk art styles from the 90s, drop inspo into “PUNK EP\mood” folder

✳️ Checkpoint: Once you have 7–9 rough demos/ideas, set new, SMART process goals to get the songs done and the EP prepped for release.

Remember, you can — and in many cases should — alternate between DAFT* and SMART process goals as you move towards your larger creative outcome goal.

A quick, but very important aside

DAFT* process goals don’t replace the need for SMART process goals. A strong creative cycle requires both divergent and convergent forms of thinking and often requires us to bounce back and forth between creative and procedural work until we arrive at our larger outcome goal.

You can — and in many cases should — alternate between working on DAFT goals and SMART goals to make progress.

It may help to think of this back-and-forth like you’re on a swing. Your initial momentum is near-zero as you start pumping your legs to build energy. As you swing backward, you hurdle into the unknown with the trust that momentum will carry you through. Butterflies fill your stomach. This is the DAFT part of the process.

Then your momentum pivots as you begin racing forward, able to see everything coming at you. You feel in control. You know what to expect as you move towards the apex. This is the SMART part of the process.

And as you put in more energy, you eventually build-up to the moment you (safely) launch off the swing and soar to new, great heights. This is the arrival at your outcome goal.

Finally, for those who like to nerd out on the research on this stuff (like I do), a very recent study published in Communications Biology (Nature) points to developing evidence that “alternations between exploratory search and focused attention support creativity” [10]. This meshes with the idea above that creativity requires a back-and-forth between discovery and definition — divergence and convergence — like a pendulum.

Recap and wrap

Okay! We’ve covered some good information. Now let’s wrap up and put what we’ve covered into context!

In the broader landscape of setting goals around creativity, we now know of 3 types of goals we should set:

- Outcome goals

- DAFT* process goals

- SMART process goals

Then — to make our goals work for us — we combine them in this order:

- Set an outcome goal — your big milestone

- Set DAFT* process goals and repeat them until you’re ready to…

- Set SMART process goals and repeat them until you either

- Have a need for more creative material and set more DAFT goals

- Reach your outcome goal!

And there it is. I hope some of this outline is useful to you and positively impacts your creative process.

–J

References

[1] T. Miller, “Process Goal vs Outcome Goal: How to Use Them for Success,” Lifehack, August 26, 2021. [Online] https://www.lifehack.org/901864/process-goal-outcome-goal.

[2] G. T. Doran, “There’s a S.M.A.R.T. way to write management’s goals and objectives”. Management Review, vol. 70, no. 11, pp. 35–36, 1981.

[3] B. J. Zimmerman, and A. Kitsantas, “Developmental Phases in Self-Regulation: Shifting From Process Goals to Outcome Goals,” Journal of Educational Psychology, vol. 89, no. 1, pp. 29–36, 1997.

[4] Wikipedia Contributors, “Convergent thinking,” Wikipedia, April 14, 2022. [Online] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Convergent_thinking.

[5] Wikipedia Contributors, “Divergent thinking,” Wikipedia, May 18, 2021. [Online] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Divergent_thinking.

[6] A. D. Fredericks, “Why Kindergartners Are Better Creative Thinkers Than Graduate Students,” Psychology Today, September 24, 2021. [Online] https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/creative-insights/202109/why-kindergartners-are-better-creative-thinkers-graduate-students.

[7] E. A. Locke, and G. P. Latham, “New Directions in Goal-Setting Theory,” Current Directions in Psychological Science, (15) 265. October 1, 2006. [Online serial]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00449.x

[8] G. H. Seijts, and G. P. Latham, “The effect of distal learning, outcome, and proximal goals on a moderately complex task,” Journal of Organizational Behavior, vol. 22, issue 3, pp. 291–307, April 20, 2001. [Abstract]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1002/job.70.

[9] E. A. Locke, “Motivation through conscious goal setting,” Applied & Preventative Psychology, no. 5, pp. 117–124, 1996. [Online serial]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0962-1849(96)80005-9

[10] M. Ovando-Tellez et. al., “An investigation of the cognitive and neural correlates of semantic memory search related to creative ability,” Nature: Communications Biology, June 16, 2022. [Online serial]. Available: https://www.nature.com/articles/s42003-022-03547-x